Online or offline, we humans are by nature a social animal. For many of us, the quality of our interpersonal relationships is the single most important factor that determines our happiness in life. All the more so in Korea, where its society functions mostly through very personal relationships. The recent “very Korean” tear-jerker “Our Blues (우리들의 블루스)”, set against the backdrop of a tight-knit oceanside community in exotic Jeju Island (제주도), vividly shows you how ordinary Koreans cope with relationship conflicts and breakdowns among family and friends. After watching all 20 episodes of dramatic embroidery of human relationships in variegated colors – high school sweethearts, friends with ups and downs, single fathers and children, sisters with disabilities, grandma and granddaughter, and mother and son – you will better understand the soul of Koreans as intense expressionists who just can’t hide their emotions. And you will see how Koreans forgive, after all. Of course, with an empty box of tissues right beside you.

DISCLAIMER: I take no responsibility for any diplomatic fiasco or unintended obligations from legal disputes (e.g., car accidents) that you may get yourself into after reading this article.

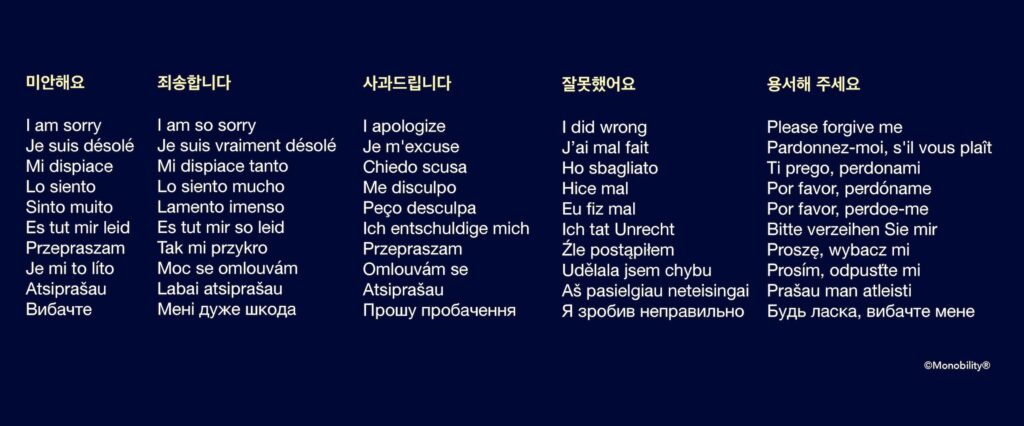

In many relationships, the first step to resolving conflicts and breakdowns would be to say “Sorry,” which seems to be the hardest word for some people. From my own life experiences, I found that some people never say “sorry” no matter what, and that others abuse the word by saying it unnecessarily too often. And for some, a simple “sorry” is enough as an apology, while for others, it’s not “sincere enough” to forgive. The reason is that every person, country, and culture has different sets of social code in apologizing and forgiving. As in some other countries, Koreans use several levels of apologies according to situations AND the relevant relationships. I listed below five most common ways to apologize verbally in Korean, with roughly corresponding phrases in other languages. In the increasing order of sincerity and gravity of the cause:

미안해요 < 죄송합니다 < 사과드립니다 < 잘못했어요 < 용서해 주세요

In one of many unforgettable, heartbreaking, sublimating scenes from Our Blues below, the son gives his father a desperate back hug, saying “잘못했어요, 아빠.” (I did wrong, Dad). Here, “잘못했어요” can not be replaced with any other apology phrase in the list above. It would be inappropriate, or awkward at least, in Korean. The reason is that traditional families in Korea educate their little children by telling them to say “잘못했어요” when they did anything ethically wrong, or hurt other people. Often times, the scolded children are supposed to kneel down, too. This is the reason why 잘못했어요 is probably the most sincere apology to Korean ears, when the cause is something intentionally wrong and unethical or something gravely affecting other people. To see the effectiveness of this one simple sentence, just watch how the dad’s hands move in the video.

- 손님, 저희가 잘못했습니다. 진심으로 사과드립니다. Sir/Ma’am (Dear Customer), we did wrong. We sincerely apologize.

This profound, crystal-clear, and sincere sentence is often followed by 용서해 주세요 (Please forgive). Just with those two sentences, if spoken spontaneously from the heart, most Koreans would forgive.

- 아버님, 제가 잘못했어요. 용서해 주세요. Dad, I did wrong. Please forgive me.

- 할머니, 저희가 큰 죄를 지었습니다. 잘못했습니다. 부디 용서해 주십시오. Grandma, we committed a big sin against you. We did wrong. Please forgive us.

Linguistically, 잘못했어요 is composed of two words: 잘못 fault, guilt + 하다 to do; 했어요 did (past tense of 하다) = literally, “I did wrong” “It is my fault.” You might find quickly that the sentence is pronounced as [잘모태써요]:

- Last consonant pronunciation rule: 받침 ㅅ, ㅆ, ㅈ, ㅊ, ㅌ as [ㄷ]

The final consonant that ends a syllable is called 받침. As a stand alone word, the 받침 may be pronounced differently from its written sound. For most beginning learners, it is sufficient to know one rule: ㅅ, ㅆ, ㅈ, ㅊ, ㅌ as a 받침 is pronounced as a quick stopping ㄷ [d].

- 잘못 fault => [잘몯], not [jalmoss]

- 낮 day => [낟], not [nadj]

- Consonant assimilation I 자음동화 1: ㄱ, ㄷ, ㅂ, ㅈ + ㅎ => ㅋ, ㅌ, ㅍ, ㅊ (Aspirates)

When the consonantal sounds [ ㄱ, ㄷ, ㅂ, ㅈ ] are immediately followed by ㅎ, their sounds become corresponding aspirate consonants [ ㅋ, ㅌ, ㅍ, and ㅊ ] (격음화 현상):

- 잘못 => [잘몯] + [했어요] => [잘모태써요]

[ㄷ] and [ㅎ] collide and sound as [ㅌ]. The other 받침 “ㅆ” in 었 keeps its sound value as [ss], since it is followed by a vowel (어), not by another consonant, and it’s not a stand alone word.

Please check out my previous video on the consonant assimilation into aspirates:

그래서 니 어멍* 갈 때도, [ 어멍 = 엄마 in Jeju Island dialect ] That’s why, when your mom left us,

아무 말 안 하고 보냈지만, 새끼야 I let her go without saying anything, dude

나는 너한테, 너한테, 이 새끼야, But to you, to you, dude,

하늘을 우러러 잘못한 게 없어, 이 새끼야 I swear to God that I have never done anything wrong to you [ “하늘을 우러러” is a poetic phrase from Korea’s most famous poem “서시 (Prelude)” by 윤동주 ]: http://monobility.com/서시-prelude-by-윤동주/

너는 세상 아무 것도 없는 나한테, 이 새끼야, To me, who have nothing but you in this world,

(이네 안캉???)* 어느 거보다 자랑이었어 [ *Jeju Island dialect is so different from standard Korean that even native Korean speakers often can’t understand it – I don’t know what 이네 안캉* exactly means here. My apologies. ] You’ve been my pride more than anything

근데 이 아방*이 쪽팔려? [ 아방 = 아버지 in Jeju Island Dialect ] And you’re telling me that I am an embarrassment to you?

이제 이 아방* 아들이 아니냐? [ 아방 = 아버지 in Jeju Island Dialect ] And now you are not even my son any more?

그래, 이 새끼야! Fine! You son of a bitch

평생을 보지 말자, 야 이 새끼야! Let’s not see each other ever again in this life, you bastard!

잘못했어요, 아빠 I did wrong, Dad

잘못했어요 I did wrong, I am sorry

잘못했어요, 아빠 I am so sorry, Dad

– 우리들의 블루스 Our Blues (2022) Ep. 8

Music: Giacomo Puccini (1858 – 1924), “O mio babbino caro,” Gianni Schicchi (1918) – Renée Fleming, Berliner Philharmoniker

Enjoy Monobility® Group for much more: