Poetry inspires us to learn more about a foreign language or culture, once we learn some basics. It is a great idea to start with poems and poets that are loved the most by the people who speak the language. When most of the country’s populace, generation after generation, love a particular poem, there must a reason for that. It is wise to pay attention and try to understand its significance, if your interest in the country continues.

For Koreans, one of such poems is 서시 (Prelude) by 윤동주. In fact, it is the prelude (or prologue) to his collection of 31 poems, written in 1941, published posthumously. He was a university student in Kyoto when the Japanese police arrested and imprisoned him in 1943 for alleged involvement in Korean Independence and Resistance Movement against Japanese Occupation of Korea. The poet died in 1945 at the age of 27, in a prison at Fukuoka, Japan, for reasons suspected to be medical experimentation with saltwater injections.

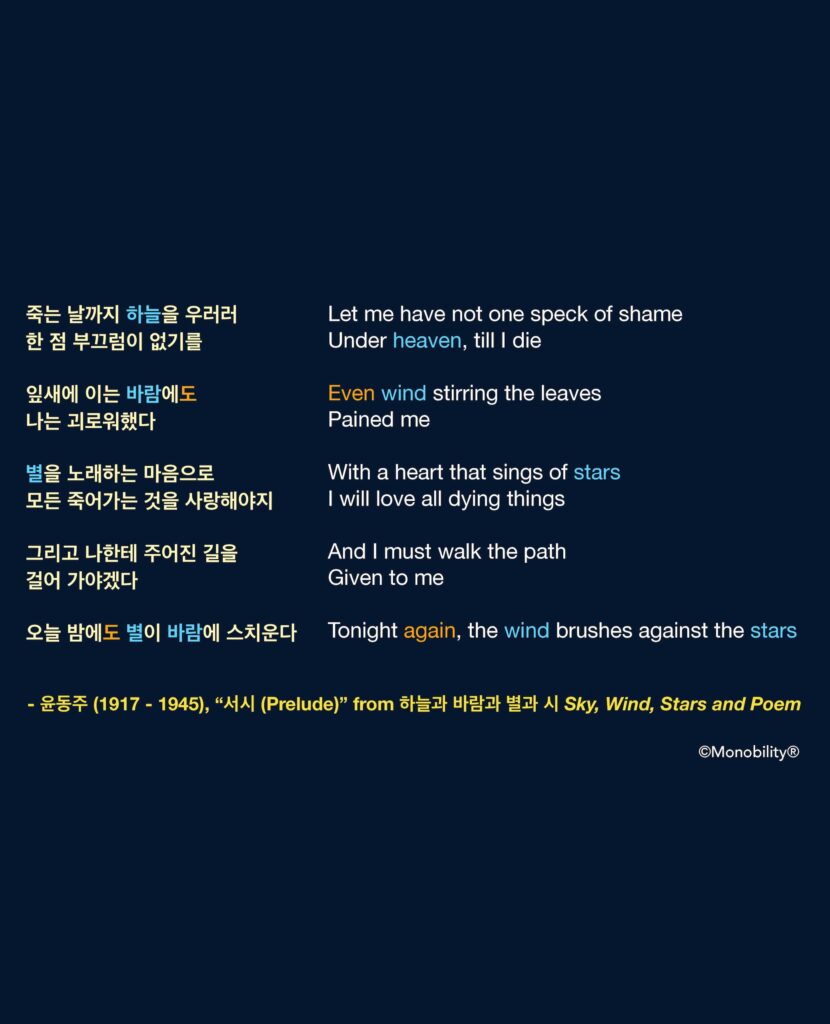

With its purity and simplicity condensed in nine lines, 서시 introduces all the rest of 31 poems in that posthumous collection titled “하늘과 바람과 별과 시 (Sky, Wind, Stars and Poem)” into the heart of readers. As a prelude, it contains all the key words in the collection title – 하늘 (Sky, Heaven), 바람 (Wind), and 별 (Star/Stars). And of course, 시 (Poem) is obviously 서시 itself. What did the poet want these words to symbolize? What did he mean by 나한테 주어진 길 (Path given to me)?

Only you as a reader would be able to tell. Some knowledge on modern Korean history would be helpful. Here is a tip: Suppose you are 23 years old, born without your own country, as your country was lost to your neighbor. You are not allowed to speak or write in your own language in public places, let alone anything against your neighbor who invaded and occupied your country some 30 years ago. And you are a poet. You are writing in your own language, 한글. Secretly.

Only you as a reader would be able to tell what 윤동주 wished to say about his innermost world to you, to the entire world, almost a century later.

Back to our usual business, the ending -도 after a noun/pronoun or an adverbial phrase means “also, too, or even.” Sometimes it can be best translated as “another, or again” in English. This usage of -도 is different from the other -도 after a verb or an adjective, which makes a clause of “concession.”

- 너도 시 쓰고 싶어? = Do YOU want to write poems, too? (You, too, you want…)

- 오늘 밤에도 하늘에 별이 많구나 = Tonight, too (again,) there are a lot of stars in the sky.

- 겨울에도 여기서는 장갑을 안 껴요 = Even in Winter, we don’t wear gloves here.

Here is my question for you now: 당신한테 주어진 길은 무엇입니까? (What is the path given to you?)

Note: As you can imagine, it is not a trivial task to translate poems. As with song lyrics, many random translations of Korean poems are available online, but they are often incorrect. Furthermore, for language learners, it is important to maintain word-for-word translation as much as possible, despite inherent structural and syntactic differences between Korean and English. The key here is to keep the right balance between making sense in English and being truthful to the original Korean way of saying things. A promising compromise it is.

Follow us on Facebook for much more: